- Home

- Maryse Wolinski

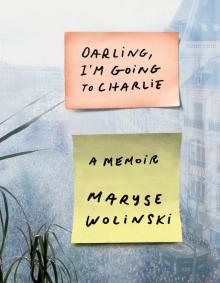

Darling, I'm Going to Charlie

Darling, I'm Going to Charlie Read online

Thank you for downloading this 37 Ink/Atria eBook.

* * *

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from 37 Ink/Atria and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Dans mon chagrin rien n’est en mouvement

J’attends personne ne viendra

Ni de jour ni de nuit

Ni jamais plus de ce qui fut moi-même.

—Paul Éluard, “Ma morte vivante” in Le temps déborde

1

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 7. I open my eyes and daylight begins to chase away the darkness. My mind hovers for a moment between consciousness and the world of dreams. I listen to the muted sounds in the apartment. The wind whistling in the fireplace. A ray of light crosses the ceiling, a car passes by the building. In the hallway, I can make out the sound of footsteps gliding along the floor: Georges is already up. Will I jump out of bed to hold him tight, or wait for him to push open my bedroom door and come to me?

This man, who is mad about women—their bodies, their audacity, their voices, their fashion, their courage, their faith in whatever they decide, their strong character—this man has looked at me for forty-seven years, lovingly. A look that is penetrating and deeply moving. A look that inspires longing, confidence, a desire to live, a desire to love. A look that makes you addicted to it. A look that sometimes causes reproach: “Why are you looking at me?” Always the same reply: “Guess!” An almost daily ritual. At dinnertime, for example: I’m rushing everywhere in the kitchen, coming and going around him as he calmly sits with a glass of Bordeaux; I bring the first course, go back to the stove to prepare the rest, and he never takes his eyes off me. Annoyed, I burst out: “I can’t take a single step without feeling your eyes on me—why?” “Guess!” Or another time, in his office: Him sitting at his drawing board, me on the other side. I speak to him, he looks at me, I know he isn’t listening. Risqué images rush through his head, while I very seriously ask his advice on something topical. “You look at me but don’t listen.” He laughs and holds me close. Furious, I pull away, turn my back on him, and walk out of the room. In the mirror above the fireplace, I follow his gaze, which is fixed on my hips. But now that look is gone. And I hear his voice: “Guess!”

Was he already sitting at his drawing board that morning, finishing the page he would take to the Charlie Hebdo editorial meeting? On Wednesdays, the “Charlies” meet to put together the next issue. Well . . . nothing is ever certain with Georges. He doesn’t always go to the Wednesday meetings. If he hasn’t finished his drawing in time, he calmly completes it, leaning over his table, in his bathrobe, his hair a mess, his eyes riveted to the sheet of paper. He’s not the only one. According to him, Cabu sometimes doesn’t show up for Charlie’s little team meetings. Bernard as well. The multitalented Bernard Maris; they call him Uncle Bernard. As for the others, I don’t really know them. I read only Laurent Léger’s articles and Philippe Lançon’s juicy columns. I also feel great affection for Cavanna, not just because he discovered Georges’s talent, but also because of the values he so fiercely defended. A year before, Cavanna had been taken away by Parkinson’s disease, his final companion, the one he had known so well how to dramatize.

It’s the first editorial meeting of the year. Georges told me that Charb, the editor in chief, had asked that all the contributors be present. They were going to share an Epiphany cake, and undoubtedly use the occasion to discuss the catastrophic financial situation of the paper and its future, which was far from certain. I remember having asked Georges one day: “What would it mean to you if Charlie Hebdo closed?” He shook his head. I thought that my question wasn’t very welcome, given his sadness after he’d left the Journal du Dimanche the June before, a rejection that had remained without explanation. I insisted nonetheless, and he finally answered. “For fifty years, we’ve always managed to land on our feet, and we’ve had many hard times at the paper. We’ll find a sponsor, a subsidy, so we can keep our head above water.” He didn’t really convince me. I could see by his worried look, his weary tone of voice, that something was wrong. Salaries weren’t always paid at the end of the month, and even if the check came, he had to wait a while before putting it in the bank. Where had those glorious years gone, the 1980s, when Choron would give everyone a raise whenever he felt like it? I could tell that Georges was worried about the paper’s situation. But he put up with it. And he missed the fraternal, jovial atmosphere at Charlie Hebdo when Reiser, Gébé, Cavanna, and Choron were there.

At four o’clock, he planned to meet me to view an apartment, since we had agreed to leave our current one, which we liked so much. We had been happy there, in our fashion. We’d moved in six years before, with the idea of staying as long as possible. Neither of us liked being thrown out of our nest. We are at a disadvantage when it comes to moving. In forty-seven years, we’ve had only three apartments. We didn’t want to move any more. But a few months before, our landlord had decided otherwise. He was taking the apartment back for his son. In the place before, where we had lived for thirty-five years, that owner had also announced one fine day: “I’m taking it back for my son.” A real wrench. We’d left our youth there.

And so today, the same scenario was being played out. Toward which horizon should we fly? We dealt with it very halfheartedly; we had no desire to leave the plane trees lining the boulevard. Me in particular. Opening the windows and seeing trees was like being in the countryside. For Georges, it was the layout of the place that he’d grown attached to. But actually he could live anywhere, as long as he had his drawing board, the one he went to the United States to buy, for it was “only in the United States that they know how to design drawing boards”—at least the ones he liked. I remember the day he came back from Washington, his board folded under one arm, a suitcase under the other. He was mad with joy.

After getting washed, I rushed into the kitchen to get my breakfast ready. I had only had a few hours’ sleep, as usual. But that never stops me from getting a good start to the new day. Perhaps we’d visit the apartment of our dreams, along the quayside. Up to now, we’d seen only pictures of it. Actually, we had already decided: the apartment we’d seen on Monday afternoon that looked out over a boulevard. The real estate agent couldn’t find the electricity meter, so we’d looked around in the semidarkness. But we liked everything: the layout of the rooms, which worked with the way we lived and worked, the high windows—two apartments in one, a balcony for my flowers, plane trees below, and undoubtedly a flood of light pouring in during the daytime. We were considering signing the lease quickly. We had a very nice lifestyle, too nice, and since we’d sold our second homes and never thought about how much money we spent, we would be renters for life. Who cares! We loved each other.

Footsteps in the hallway coming closer. This time, it really is him: Georges, my Georges. He comes in, wrapped in his black terry cloth bathrobe; on the back, it says, “My very own Zenith.” From the name of the TV program on Canal Plus he worked on with Michel Denisot. Georges drags his feet a little and walks bent over, as if he were carrying the weight of some heavy, guilty secret. Sometimes I catch him walking like that, like an old man, and I wonder what is worrying him so much. Is he suffering because he isn’t completely like everyone else, because he is an artist, a real one, so often on the margins of reality? Does he have secrets? That question gnaws at me. This morning, more than ever, his eyes are looking inward, and his thoughts are buried inside him. “Are you all right, darling?” He mumbles a yes, which means both yes and no. Then he picks up the coffeepot and says: “And you? Did y

ou sleep?” “Yes . . . Well, no, as usual.” “Did you go to bed late?” “Yes, too late, the meeting went on forever. Why didn’t I get a loving Post-it note last night when I got home?”

The Post-its tell our whole story. They cover the back wall of the kitchen. They speak of his love, his tenderness, his joy when everything is going well, his sadness when his troubles increase. Recently, the fact that his daughters were distant upset him. My women friends envied me for these little notes that came so often. It’s true that last night, I was disappointed not to find one on the table in the hall. Tuesday night’s Post-it. Too tired to think of it? These past weeks, I’ve found him morose, lost in his thoughts, his eyes dull. “Is it because of the apartment?” “No, no, it’s good, actually, to have a change. We’ll try to make some savings and we’ll start a new life . . . I think about your future a lot. When I’m no longer here . . .” I sing my old favorite song again: “Instead of dwelling on it, you’d be better off doing something. Is it what’s happening at Charlie Hebdo that’s bothering you?”

He puts down the coffeepot and reaches out to me, and his only reply is to stroke my cheek. While I get my breakfast tray ready, he sits down with his awful milky coffee and dips his bread, dripping with butter and jam, into it. Then we open our datebooks and compare our days. I remind him about the appointments we have together. On this occasion, this January 7, we’re viewing the apartment on the quayside. “Can you see yourself living there?” he suddenly asks. “No, I prefer the one on the boulevard.” “Well then, why are we going?” “Georges, I’ve made the appointment, and we have to see more than one before deciding.” He gets up, comes back with the newspaper, Le Monde. He reads an article out loud, then comments on it. These morning meetings are often my favorite part of the day. But today he’s in a hurry. The critique will be short. Before leaving the kitchen, he blows me a kiss and goes to get ready.

“Darling, I’m going to Charlie!” he says a few minutes later, shouting from the other end of the apartment. Then he returns, pulls back the curtain that separates my bedroom from the bathroom, and pops his head inside. “Darling, I’m going to Charlie.” It must be nine o’clock, I’m late, still wrapped in my bath towel, not paying much attention to him. I recall thinking that he was leaving earlier than usual for a Charlie meeting. I hear his footsteps in the hallway, then the door slam shut. At that moment, I always feel slightly sad. But today, I know we’re going to see each other again that afternoon, at four o’clock.

2

AT TEN O’CLOCK, I go to my Wednesday exercise class. I didn’t tell Georges about my concerns over the possible closure of Charlie Hebdo. I know that, for him, such a decision would mark the end of a long, great adventure that started when he came back from the Algerian War. Even if he is not always in agreement with certain ideas, certain polemics developed in the newspaper, even certain caricatures, he remains, and would always remain, loyal. He left L’Humanité and Le Nouvel Observateur, but he would never leave Charlie Hebdo as long as the paper existed. Reiser died, then Gébé, then finally Cavanna, in 2014. Each time, he lost a brother. Now the death of the paper itself threatens to strike him. Why can’t Charlie get readers? Is it an effect of the way society is evolving, which leaves Georges so perplexed? Fifty years of fighting for freedom of expression just to be faced with uneducated people, barbarism, and Sharia law. Once again forced to ask the question “Is it possible to laugh at everything?” Georges chose his camp: the laughter of resistance.

All this is going through my head while I’m trying to relax my body. Eleven o’clock and the class finishes. I head for a meeting and turn off my cell phone.

Around eleven fifteen, on rue Nicolas-Appert, Thomas, an actor and director, is loading scenery onto a truck parked in the alleyway of the Comédie Bastille theater, opposite number 10; it’s scenery from the play he directed and acted in for several months, Visiting Mister Green. He’s in a hurry to load the truck; another theater in Avignon is expecting him for a meeting. It’s about to snow, and the journey looks as though it will be difficult. Nathalie, the dresser at the theater, as well as Julien, the stage manager, are giving him a hand. The evening before, they sadly watched the last performance of the play, which never really found its audience. Thomas stays inside the truck while Nathalie and Julien go back and forth to load the various pieces of scenery. A black Citroën races out of the boulevard Richard-Lenoir and onto the street, its tires screeching. Startled, Thomas sticks his head out of the truck; the driver of the car is staring at him. Thomas will never forget the way he looks at him, like a wild animal.

Like Thomas, Joseph, a worker from a nearby construction site, observes the car that parks at the corner of the allée Verte and the rue Nicolas-Appert. Doors slamming and shouting. Surprised, Joseph, like Nathalie and Julien, goes out to see what’s happening. They all can see, more or less clearly, three men in black balaclavas coming out of the Citroën. The first man, the driver, is talking with the other two, who are armed with assault weapons and wearing bulletproof vests and extra cartridges slung over their shoulders. Their voices are loud, shrill, but no one understands what they’re saying. Thomas thinks he should call the police, but something tells him that if they move, they will be putting their lives in danger. “Are they the GIGN?” Nathalie asks. Thomas and Julien also think it’s some kind of GIGN operation, even though they know that the French counterterror police units never go out in such small numbers.

The two armed men head for 6, allée Verte. The third, the driver, visibly unarmed but wearing a bulletproof vest and a balaclava to hide his face, disappears—but Nathalie, Thomas, and Julien don’t notice. “Something’s happening at Charlie Hebdo,” Thomas says. All three of them hide behind the truck. Nathalie, a fan of Charlie Hebdo when she was young, is surprised. “Is that where they work?” she asks. “There was a police van watching the building until November,” Thomas adds. His last words are drowned out by the sound of gunfire inside number 6.

The three friends barricade themselves inside the theater, where they find Marie-France, the manager. “Two armed men went into the building across the street,” Nathalie explains. “I hope they’re not going to Charlie Hebdo,” says Marie-France. “What did the armed men look like?” “Like the GIGN. We thought they were GIGN.” “Are you dreaming? If it were the GIGN, the streets in the area would be blocked off and dozens of police cars would already be here. We’d hear their sirens. Charlie Hebdo is in danger. They’ve received threats. I even think that one of them had a fatwa put on him. At least, that’s what it said in the papers.” “You’d think that given the circumstances,” Thomas adds, “the place would be protected, barricaded.” “What about the police van that’s been there since they moved in?” asks Marie-France. “It’s been gone since early December,” Thomas replies. “That’s unbelievable! Why?” Thomas doesn’t know what to say. Preoccupied by his play, he hasn’t really paid much attention to the news recently, but he did notice the police van had gone and found it strange that it should disappear at the very moment when the newspapers and radio stations were endlessly warning people about the possibility of a new terrorist attack in the capital. “Are you sure?” Nathalie asks again. “First they removed the protective barriers,” Thomas remembers, “then the police van stopped coming.” What if they were terrorists? This idea gnaws at him. Several rounds of gunfire make them stop talking. A lull, followed by another salvo. “I’m calling the police!” Marie-France returns to her office to dial the emergency services.

Laurent, the production manager for the press agency Premières Lignes, was out on the sidewalk smoking when he heard the first deafening shot echo in the silent street. He saw the backs of two men dressed in black carrying what he knew were military weapons. While they were going in through the allée Verte, he took the stairs in 10, rue Nicolas-Appert and went back up to his office on the second floor, opposite Charlie Hebdo, to warn his colleagues and, more important, to call the police. On the phone, he told them about the men in b

lack, who were armed and wearing balaclavas. He himself was unaware that Charlie Hebdo’s offices were on the same floor as his office. Their door was marked LES EDITIONS ROTATIVE. Despite the threats received by the newspaper that had been reported in the media, no sign existed in the building to warn people that the satirical publication was located there. Laurent warned the other journalists from the agency. Some of them had already run into Georges and Cabu in the corridors, or had taken the elevators with them. They knew perfectly well that Charlie Hebdo was located there. They immediately realized that the armed men were looking for the paper’s offices and reproached themselves for never having asked for their phone numbers. How could they warn them? Walk across the hall and knock on the door? Laurent remembered that in the middle of September, one of the journalists from the press agency had been smoking outside on the street when a car stopped in front of him. The driver shouted: “Is this where they find it funny to criticize the Prophet?” The journalist didn’t reply. Then the driver added: “You can tell them we’re watching them.” The journalist took down the car’s license plate number and gave the information to Franck Brinsolaro, Charb’s bodyguard. Franck sent the information to his superiors at the SDLP.I But protection for Charlie Hebdo still hadn’t been increased. They had tried to identify the driver, but it had been decided he had nothing to do with terrorism. Now he’s supposedly in a psychiatric facility.

Worried over the increasing amount of gunfire, Laurent tells his colleagues to go up to the roof using the stairs inside the building.

At eleven o’clock, Chantal, an executive saleswoman in her fifties who works for a Swiss company, steps into 10, rue Nicolas-Appert. She is just in time for her meeting at SAGAM, a company that specializes in childcare products. She is welcomed into the company’s office, on the ground floor of the building. After the usual introductions, she is shown the room where the meeting she will speak at will be held. To get there, she has to pass 6, allée Verte, the road that cuts through to rue Nicolas-Appert. On the first floor are strollers, changing tables, and all sorts of products for very young children. One of her colleagues is already there.

Darling, I'm Going to Charlie

Darling, I'm Going to Charlie